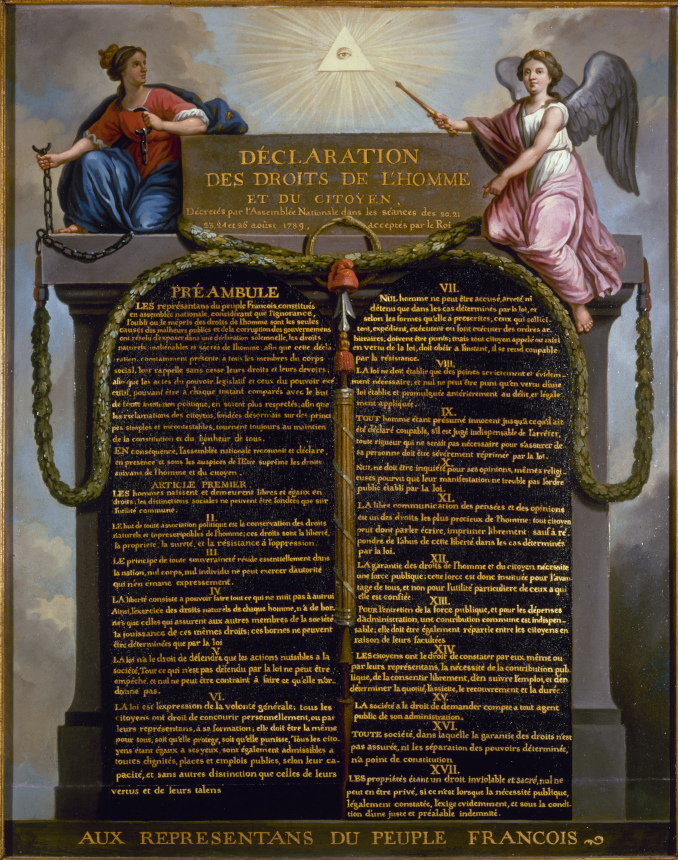

Declaration of the Rights of Man. Jean-Jacques François le Barbier (1789). Musée Carnavalet ⁄ Roger-Viollet, Paris. Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain

By Nina Heyn – Your Culture Scout

“For we fight not for glory, nor riches, nor honors, but for freedom alone, which no good man gives up except with his life.” ~ Declaration of Arbroath, 1320. National Museum of Scotland.

We are used to seeing ideologically engaged works in modern art museums. Twenty-first-century artists often address issues such as human trafficking, migration, and racial inequality, especially using the modern media of installations, videos, or shocking sculptures. In previous centuries, art was no less engaged in talking about freedom, but did so through different media. One might see a historical painting present momentous events in the struggle for national independence, while a print would disseminate immediate political and religious messages, and a genre painting would convey social messages. Poster art would have been viewed as the perfect medium for protests and agitation.

If there is one painting that people would readily associate with freedom fighting, Liberty Leading the People by Eugène Delacroix is definitely it. It is one of the most famous French artworks but also universally known as an artistic symbol of people’s right to self-determination. Delacroix belonged to a generation of European artists who, born after the 18th-century revolutions and the Napoleonic era of great campaigns, yearned for the military grandeur of the previous era. They felt that they had missed all the action of triumphant wars and sweeping social changes, and they expressed that nostalgia in Romanticism—a movement that prized freedom above all. “I do not care for reasonable painting at all. My turbulent mind needs agitation, needs to liberate itself,” declared Delacroix. His canvases reflected that passion for independence of body and spirit.

Liberty Leading the People (La Liberté Guidant le Peuple). Eugène Delacroix (1830). The Louvre. Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain

Delacroix painted Liberty Leading the People to celebrate the Paris revolt of 1830 that led to the deposing of Charles Χ. The king wanted absolute power even though this desire had already cost his older brother Louis XVI his head, but the people of Paris would have none of it. They did not want to go back to the ancien régime. Delacroix’s painting is allegorical, presenting symbols rather than real people, all of them united in storming a Parisian street, with the city identified by Notre Dame’s towers in the background. The working class is represented by a man with a pistol tucked into a tricolor scarf, and the bourgeoisie is embodied by a man in a top hat wielding a rifle—who is Delacroix himself. The revolutionaries are led by a goddess of Liberty, posed like an antiquity statue but at the same time completely updated for the artist’s times. She is wearing a Jacobin red cap, raising a national tricolor flag (created during the French Revolution), and holding a weapon that is no longer a sword but a bayoneted rifle. Following Charles Χ’s ouster, the new government of King Louis Philippe bought the painting to acknowledge the “courageous barricade fighters” but then discreetly put it away so as not to give any bad ideas to the people it glorified. France had already learned at the beginning of that century that too much revolutionary spirit was a dangerous thing for those in power.

Delacroix also painted another passionate and instantly famous commentary on political events. Painted in 1824, The Massacre at Chios is almost a political reportage, portraying an event from two years prior when Turkish soldiers massacred Greek civilians on the island of Chios. In fact, the plight of Greeks rebelling against Turkish occupation has resonated with many European artists and intellectuals, including Lord Byron, whose engagement there cost him his life.

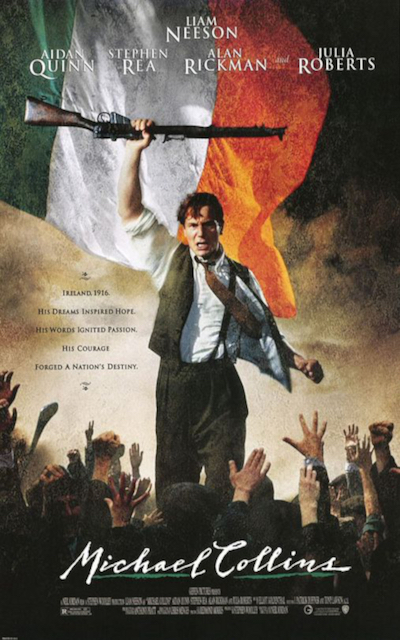

Delacroix’s image of a dash to freedom in Liberty Leading the People has inspired other artists up through the present day. Already in 1884, a French artist named Ernest Meissonier painted The Siege of Paris 1870-71, which was in direct dialogue with the Delacroix work. Later, some of the propaganda posters for the Russian revolution and WWII evoked the same flag-wielding image. As recently as 1989, a poster for the movie Michael Collins (about a leader of the Irish independence movement) again directly referenced Delacroix symbolism.

The 19th century in Europe was the age of independence movements all over the continent. While the citizens of France or Britain fought over their civic rights or engaged in internal conflicts pitting the ruling classes against the proletariat, numerous places in Europe were battling for more basic rights to their sovereignty as nations. The Irish were chafing under British rule, Italian principalities were trying to form a unified country, and the Balkan states were shaken by periodic uprisings against the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman empires.

Poland presents an extreme example of the loss of national freedom in Europe. A large and once-powerful country, for various reasons it lost its sovereignty for the entire 19th century, regaining political independence briefly between the First and Second World Wars, only to lose it again for a big chunk of the 20th century with the Soviet Union’s political takeover of Eastern Europe. Due to this historical context, Polish art abounds in patriotic canvases that either glorify episodes from independence battles or are nostalgic recollections of the heroic past. Nineteenth-century painters Jan Matejko and Juliusz Kossak provide examples of both approaches.

Realist painter Jan Matejko devoted his life to portraying episodes from Polish history and literature to educate the nation and sustain patriotic fervor. The Battle of Raclawice depicted a victorious engagement of the Polish army against Russian troops when Poland was opposing its annexation in 1794. For American viewers, this painting forms part of their history, too, since the man leading this insurrection was Tadeusz Kosciuszko, who had become a decorated hero of the American Revolution a few years earlier. In this painting, he is the horseman in a green coat, waving a hat and surrounded by several famous personages of that Polish-Russian war.

The Battle of Raclawice (Bitwa pod Racławicami). Jan Matejko (1888). Sukiennice Art Gallery, Kraków. Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain

These days, we would call such a canvas a propaganda poster or perhaps a “genre” story in the style of Norman Rockwell—for these are not real people but icons of freedom fighters who are fulfilling their patriotic duty. Moreover, although the title says “battle,” what we actually see is the victorious aftermath, with Polish combatants waving arms while the vanquished, red-clothed enemy soldiers are lying on the ground.

Matejko also painted other historic battles, including an impressive canvas titled The Battle of Vienna that is displayed at the Vatican Museum. We can also take a look at the different treatment of the same theme by another Polish artist, Juliusz Kossak, a Matejko contemporary famed for his nostalgic military and hunting scenes as well as compositions that praised the Polish military past. The Battle of Vienna is not only an important chapter in Polish military history but also an event that impacted the fate of Europe. In 1683, when armies gathered near Vienna to face Ottoman troops led by Grand Vizier Kara Mustafa, it was more than a purely military encounter. Had the Turkish army won the day, modern Europe would not look the way it does now, and many countries in central or eastern Europe would possibly have become at least partially Muslim (like Bosnia or Albania). The battle of Vienna was, therefore, not only a fight for territory but also a clash of opposing religions and cultures. Defending Vienna was the army of the Holy Roman Empire, commanded by Jan III Sobieski, the King of Poland, who unleashed 18,000 armored horsemen in the largest cavalry charge in history. The king personally led 3,000 winged hussars (heavy-armored knights who sported scary-looking wings) on a surprise attack out of a forest. The Ottomans did not expect this ferocious assault and dispersed. The winning armies took over Kara Mustafa’s camp and, in the long run, ensured a halt to the Ottoman empire’s advance on the continent. Sobieski, one of the rare royals on very good terms with his wife, reported to her after the battle: “Ours are treasures unheard of . . . tents, sheep, cattle and no small number of camels . . . it is victory as nobody ever knew before, the enemy now completely ruined, everything lost for them. They must run for their sheer lives.” In Kossak’s painting, the victorious King Sobieski (center left, in red hat) is greeting one of his winged cavalrymen, carrying a trophy of a green Turkish vizir’s flag.

King Sobieski at Vienna (Sobieski pod Wiedniem). Juliusz Kossak (1882). National Museum in Warsaw. Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain

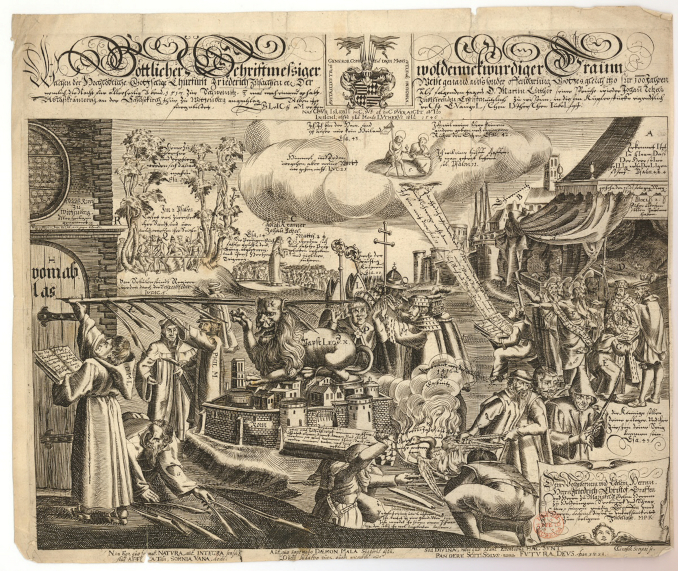

It often takes decades for people to look back and understand the importance of some event in their own lives or in the history of their community. In the year 1617, exactly one hundred years after Martin Luther hammered his religious protest to the church door in Wittenberg and started the Protestant Reformation, the German Duchy of Saxony decided to celebrate the centenary of the event. This is one of the earliest examples of the public celebration of centenaries, replete with processions, fairs, souvenir medals, and printed materials. The broadsheet shown below—a souvenir flyer, political cartoon, and propaganda poster rolled into one—was created barely a year before the start of the Thirty Years War, a devastating religious conflict in the middle of Europe that proved that co-existence of different religious views is better than an unresolvable pitting of two faiths against one another. Unfortunately, as modern religious conflicts show, this is a history lesson that has not been very well absorbed.

Reformation Centenary Broadsheet. Conrad Grale and Jonathan Glück (1617). British Museum. Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain

On the broadsheet’s right side is Luther, in direct contact with the divine Trinity, reading the Bible in the light connecting him with the heavens. On the left, there is Luther again, writing Vom Ablass (”About Indulgencies”) using the biggest quill pen ever, which, not incidentally, is topping a crown off the pope’s head. The pope is also presented in the symbolic form of a beast sitting on Rome’s walls. Pope Leo X and Rome are captioned to ensure that the information is clear. Luther, through his direct contact with God’s word in the Bible, gains religious wisdom and knocks down the Vatican’s dominance. The broadsheets would sell for a few coins at fairs and markets and would be posted at public buildings, serving to remind the people of Saxony (and their ruler) that the religious freedom of communicating with God needed to be protected. The pen might be mightier than the sword, but in an era when a large part of the population could not read, a good drawing would have been even mightier than a pen.

In Victorian England, the demand for women’s voting rights started through the protests of Emmeline Pankhurst and was subsequently taken up by women’s suffrage groups in other countries, becoming one of the most famous and hotly debated human rights issues of the day. This celebrated political cause perhaps obscured another issue pertaining to women’s independence—a financial one. At the time, there were few opportunities for middle-class women to earn money. Most could not own property and were financially dependent on their fathers and then husbands. If these resources were not available to them, they had to seek positions as servants, clerks, or nannies. Englishwomen’s lack of financial freedom did not really change until the First and especially the Second World War, when women attained more access to workplaces.

The Governess. Emily Mary Osborn (1860). Yale British Art Center. Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain

Emily Mary Osborn made her name in the mid-1800s as a painter of middle-class women in difficult circumstances. Nameless and Friendless, her most famous painting, depicts a widow trying to sell her valuables while being ogled by the shop customers. Another canvas, called The Governess, is a perfect depiction of the humiliating life of a nanny in a grand house. There, we see a young woman being scolded by the mother. A little boy points his accusing finger, secure in his knowledge that his transgressions will be blamed on the powerless nanny. The other kids’ sniggering expressions prove that they have already learned that their governess has little standing in this household. Osborn’s aim was a moralistic one and, as an illustration of the plight of “decent but poor” women, the painting was very popular—in fact, Queen Victoria purchased it for her art collection.

Guernica. Pablo Picasso (1937). Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid. Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain

In modern times, no other painting symbolizes modern warfare’s devastation more than Picasso’s Guernica. When he painted it in 1937, Picasso was no longer the young, bohemian artist in Montmartre who had experimented with distorted images and papier collé on the eve of the First World War. He had already given the world the idea of deconstruction in his seminal Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907), had invented Cubism with Braque and created Ma Jolie in 1908, and had been through his periods of neoclassicism and surrealism. Nor was he any longer the helpless immigrant who was afraid of deportation after a statuette he bought from Apollinaire’s assistant turned out to be stolen from the Louvre.

By the late 1930s, Picasso was famous enough to be invited to create a painting for the Spanish Pavilion at the International Exhibition in Paris, but… he was still an immigrant and was turning his gaze toward his native land. Spain was in the throes of a Civil War, and cities were being destroyed by Luftwaffe bombings. One such place was the Basque town of Guernica, and the shocking massacre of civilians that took place there became the theme of his mural. The artist took the classical structure of a history painting—a central pyramidal arrangement—and filled it with symbols of the tragedy of war: a fallen soldier with a broken sword, a woman holding a child, a maimed horse. The artwork was in striking black and white, echoing the press coverage of the time and, at the same time, very unusual for any finished painting. By the time the Second World War came around, Guernica had become an established 20th-century image of anti-fascist and anti-war protest. There is a possibly apocryphal story about Picasso being visited in his Paris apartment by a Nazi officer during the occupation. Spotting a photograph of Guernica, the officer asks, “Did you do it?” “No,” replies Picasso. “You did.”

“Freedom” means different things to different people, and artists are no exception. No matter how hard it is to show abstract notions like independence or freedom in paintings, artists have found ways to express their opinion. In ages past, they might show it to you in a historical allegory or social satire. In modern times, these concepts could be expressed as Kara Walker’s black and white silhouettes, Cai Guo-Qiang’s fireworks, or a Banksy mural.